American elections brought a sigh of relief. Israel elections did not. What does it teach us about human nature?

What do we do when it feels like half the world is consumed by hateful, callous ideas? I have some thoughts.

I was participating in a team-building exercise recently when the facilitator said something that shocked me – and just when I thought I couldn’t be shocked anymore.

“You can’t teach empathy,” she said, with complete confidence.

The group had just finished one of those personality inventories in which we each had to give ourselves a label that described our essential core types. When one of our leaders asked, “Can our personality type change over the course of our lives?” the facilitator responded curtly, “No.” Someone chuckled about “the old nature versus nurture” debate, as if there is no point in trying to resolve it, and we promptly moved on. Then, as the facilitator scrolled through the list of nine personality types, she came to one that she said describes “many bosses” – that is, people who never give positive feedback, who over-demand their employees’ time and energy, or who perhaps pull an Elon Musk and fire anyone deemed insufficiently “hard core”. Many in the group nodded in recognition.

But when she followed up with the idea that these behaviors are innate and immutable, I perked up. “These people, they are born this way,” she said. “They can’t change.”

“Do you realize what you’re implying about humanity?” I asked. “That we can’t teach empathy? That if we’re not born with it, we’re done for? That’s a terrible indictment.”

She laughed. “Trust me,” she said. “Have you seen what is happening in the world?” This was a few days after the Israeli election, when the racist, sexist, homophobic, and possibly fascist party of Ben Gvir got an astounding 14 seats. And also, by the way, after six year of Trump dominating America.

“Touché”, I said.

I recognize the sentiment. I know well the frustration of trying to have a reasoned discussion with people who are unmoved by human suffering. It does sometimes feel like people who have abandoned empathy as a lifestyle cannot be returned.

But actually, despite the temptation to believe that, it’s actually wrong, at least for the most part. Certainly some 2-6% of the population comprises narcissistic psychopaths, and possibly increasing — alarming, I agree — but as the saying goes, tough cases make bad law. For the other 95%, empathy can and should be taught.

Obviously. Of course this is true. If we couldn’t teach empathy, why would we bother educating our children, engaging in debate, or working towards social change? If people were born with the entire capacity they will ever have to feel another person’s pain, why would we try influencing anyone else ever?

We do these things because human beings have always lived on the assumption that a change of heart is possible – perhaps inevitable – and maybe even at the core of the human condition.

******

The idea that people can’t change who we are is easily refuted. People change all the time, even every day, sometimes intentionally and sometimes as a result of life’s unanticipated torments. We read, we study, we learn, we grow. That is what makes us human. This process of human transformation dominates pretty much every novel and movie that we consume. We love stories about people grappling with life in a way that challenges who they think they are, and coming out changed, better. It’s called a story arc. And it absorbs us. It is who we are and what life is all about.

Despite this overwhelming evidence, many people go to great lengths to put other people in stultifying boxes and tell them that they are who they are and who they will always be. That’s such a shame. In my doctoral dissertation in sociology/anthropology at Hebrew University, I studied the kinds of labels that many cultures put on people, the “boxes” that we are often put in. I looked at issues such as gender, and the way a person’s biological gender is often used as an excuse to make essentialist determinations about people’s personalities. Like, if you are born with a uterus, you are innately predetermined to be natural “mother material”. I am sure that many of those who nodded along about the boss with no empathy can attest that this is certainly not the case. Women can be as cruel as men (Kary Lake anyone?).

In my post-doctoral research, which eventually became my first book, The Men’s Section, I explored the way Orthodox men are also put into boxes. Orthodox culture generally assumes that people born with male genitalia are automatically good Torah readers and Talmud scholars who enjoy engaging in thrice daily group rote-prayer exercises. My research suggested that many Orthodox men grapple with these cultural expectations and constructs, though they often do not have the language to explain why these essentialist determinations do not work for them. Instead, they often end up feeling like they are just “different”.

This example is a perfect illustration of how damaging the idea of predetermined personalities can be. Carol Dweck, in her must-read book Mindset, lays out these two contrasting approaches to the human condition, what she calls the “fixed mindset” and the “growth mindset”. In the fixed mindset, people believe that they are born a certain way – good at math, an amazing athlete, a gifted surgeon – and that is fatefully immutable. In the “growth mindset”, people are what they learn. Nobody is born a brain surgeon or an Olympic gold medalist. They change, they study, they practice, and they evolve.

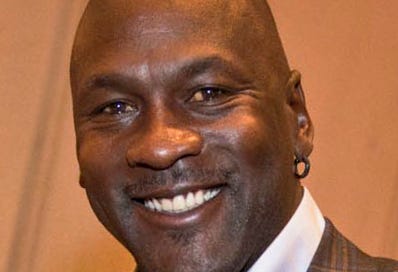

Dweck studies how these different mindsets affect people, and her findings are deeply disturbing. People with the fixed mindset are more anxiety-prone, stressed, depressive, and crushed by disappointments than people with the growth mindset. For example, if someone who thinks they are the best in math gets anything less than a perfect score, they may conclude that they have ruined their life by betraying their own destiny. By contrast, someone who has a growth mindset is free from those traps and is able to respond to imperfect performances or even failures by viewing them as opportunities to learn and improve. Failure doesn’t have to lead to suicidal thoughts. Or as Michael Jordan – Dweck’s most famous growth-mindset aficionado – said, “I've missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I've been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life.” He is okay with all that because he realizes he wasn’t born an amazing basketball player. He constantly works in order to learn to become one.

*******

I once witnessed the direct impact of educating into the fixed mindset. Years ago, when I was teaching a course in Gender Issues in Jewish Life at the Melton Adult Mini-school in Melbourne, a man in my class who I’ll call Adam raised his hand to disagree with my core assertion that our gender identities are socially constructed. “I’m a man,” he said. “It’s why I like sports. That’s why I get angry. It’s who I am. I’m a man”.

His wife, who was sitting next to him, stared at him.

I could understand why.

If a person has a habit of getting angry at his wife, and his reaction is “I can’t help it; I was born this way,” instead of, “I’m sorry, that was a mistake and I will try to do better,” that is bad.

Very bad.

This goes to the core of why the nature versus nurture debate is not just abstract or theoretical. It goes to the question of whether we have any control over ourselves, and whether we can change and be better.

If we accept a biologically predetermined version of who we are – “our nature” – then we raise our hands and give up, and accept that we can never change. Just like Adam said about his anger. Just as our facilitator said about, well, everything. We are who we are and so what’s the point of trying. No wonder people with the fixed mindset are prone to depression. The powerlessness can be crushing.

But the understanding that our personalities are constructed by our experiences – “nurture” – is an argument that gives us room to grow and change. Even if you don’t buy it 100% (and we have all seen those creepy studies about twins separated at birth who smoke the same cigarettes and wear the same brand of sneakers), the nurture argument is liberating and humane. It enables us to evolve, to learn, to change, and to be whoever it is that we want to be. And it also enables us to break out of boxes that we may have been put into without our consent.

Meanwhile, in my Melton class, Adam’s wife was not pleased – but not for the reason I had anticipated. The wife – let’s call her Eve – looked at Adam and said, “You know, we have TWO sons. Only one of them likes sports.”

Touché.

***

This whole exercise of putting people into personality labels – or any essentialist label – is so deeply wrong. I think about the person who invented the Nine Types of Human Beings chart that we were using, and I think, what incredible arrogance. Image looking at a planet full of 8 billion people and reducing them all to just nine. Nine! It is a grandiose erasure of so much beautiful diversity. Imagine meeting another person and rather than engaging with their unique life story, perspective, taste, or quirks, you go and say to yourself –or to them -- “Ah, I get you. You’re a Number Six.”

It is quite an obnoxious thing to do to another person.

And some of us have had that kind of experience our whole lives. I can’t even count how many people have tried to put me into all kinds of boxes. Sometimes it is hard for me to recognize the voices in my head telling me what I am or what I’m not – whether those are voices of family members, teachers, bosses, rabbis, therapists, or someone else. Maybe myself? Usually not. My own voice about who I am is so often drowned out by those of the zillions of other people telling me who I am that I think I’m still kind of recovering from that experience.

Which is why I didn’t take to that entire exercise particularly well.

I do think that if a person walks into a room of strangers with the goal of telling us exactly which number we are within that line-up of nine, they should at least buy us all a drink first. I think a little vodka might have helped me get through the session more easily.

I understand that team building exercises can be useful when embarking on group projects. But the entire thing could have been done without putting us all into boxes. We could have used a growth mindset instead of a fixed mindset, and used it as an opportunity to learn and grow, rather than do a ridiculous personality test.

We could have, for example, done role-plays. We could have used that example of the non-empathetic boss, and done an exercise in hashing it out. What are the helpful ways to deal with that kind of personality? I would love to know, actually.

That would have been an actual learning exercise, instead of a triggering experience bringing up a million old traumas.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Roar to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.