How is this Purim different from all other Purims?

As we emerge from two years of pandemic, into brand new forms of chaos, is there any hope of change for women?

The Purim holiday formed one of my first adventures into Jewish feminist thought. In one of my first published essays in the Jerusalem Report in March 2000, I offered an analysis of the relationship between Mordechai and Esther in the story, in which Mordechai offers his beautiful niece/cousin/wife to a powerful emperor who had a predilection for disposing of disobedient wives. I wondered out loud why we, as a community, have been adulating such a man for generations.

Purim has always been at the forefront of the Jewish feminist revolution. Women were reading the megillah before there were women rabbis in any of the denominations. The megillah reading is one of the first spaces in which women began to take back our religion.

There is also Esther herself. She is one of two biblical women who merits having a book named after her, and as such offered a rare portrait of a woman who leads. Although this portrait raises other questions of what it takes for a woman to have power. Esther was first offered as a silent sacrifice by the self-serving Mordechai, then lived for a while in a harem, and ended up prostituting herself to the megalomaniacal king. Sure, she saved her people, but it could have gone either way for her. I still have a lot of questions.

Then there is Vashti, a woman trashed vilified by men throughout history, including many of our rabbis — and then reclaimed as a feminist icon. Comedian Rachel Creeger recently did a bang-up job bringing her story to life.

There is a segment in the first chapter of the Book of Esther around the story of Vashti that offers us a painfully honest description of patriarchal forces at work.

Memuchan declared before the king and the princes, "Not against the king alone has Vashti the queen done wrong, but against all the princes and all the peoples that are in all King Ahasuerus's provinces. For the word of the queen will spread to all the women, to make them despise their husbands in their eyes, when they say, 'King Ahasuerus ordered to bring Vashti the queen before him, but she did not come.’

If it please the king, let a royal edict go forth from before him that Vashti did not come before King Ahasuerus, and let the king give her royal position to her peer who is better than she.

And let the verdict of the king be heard throughout his entire kingdom, and all the women shall give honor to their husbands, both great and small."

And he sent letters to all the king's provinces, to every province according to its script, and to every nationality according to its language, that every man dominate in his household and speak according to the language of his nationality.

This thinking, in which men have to control their wives because otherwise men will lose power not only in their homes but as a nation, has not faded from our lives. I recently argued that this thinking explains a lot about the abortion discussions happening in America right now. So there’s that.

There are many other gendered aspects of Purim that I have been observing over the years. There is the strange habit in many Orthodox communities of dressing up as the “opposite sex”, so to speak, which not only gives us a glimpse of what Orthodox men see when they see “women”, but also raises many questions about how people feel trapped in gender performances and whether Purim, with its carnival-like permissions to turn the world upside down, offers people an opportunity to break out of their gender boxes, if only momentarily. And by the way, the term “opposite sex” has still not been challenged in many corners of the Jewish world.

Some subtler, or more culturally embedded gender aspects to the holiday, are also worth observing. Such as the assumed competitions in certain corners around who delivers the most elaborate mishloach manot, or who goes to the greatest lengths with meal preparation, costume design, or other performances. I certainly applaud the women who use these customs as opportunities to play with their crafts and do it with a love for both art and giving. But that aspect of female competitiveness around religious performance is something that I stepped away from years ago and do not miss at all.

And we all know that it’s all just a dress rehearsal for the Pesach competition, which is just around the corner. Speaking of gendered servitude.

So my question today, after 25 years of observing and analyzing these cultural performances is, has anything changed? Especially now, after Covid and lockdowns, after impromptu garden synagogues and people turning inward and going for simplicity, after so much loss and death and pain, after two years of women overburdened by double and triple shifts, when we are trying to rebuild a world that looks like it may be on the verge of a cosmic crash, has anything about all of this changed? Are we doing anything differently?

I don’t know. I wish I could say, yes, we are all so much smarter and more compassionate than we once were. Maybe we are, a little. Let me know if you have seen evidence of this.

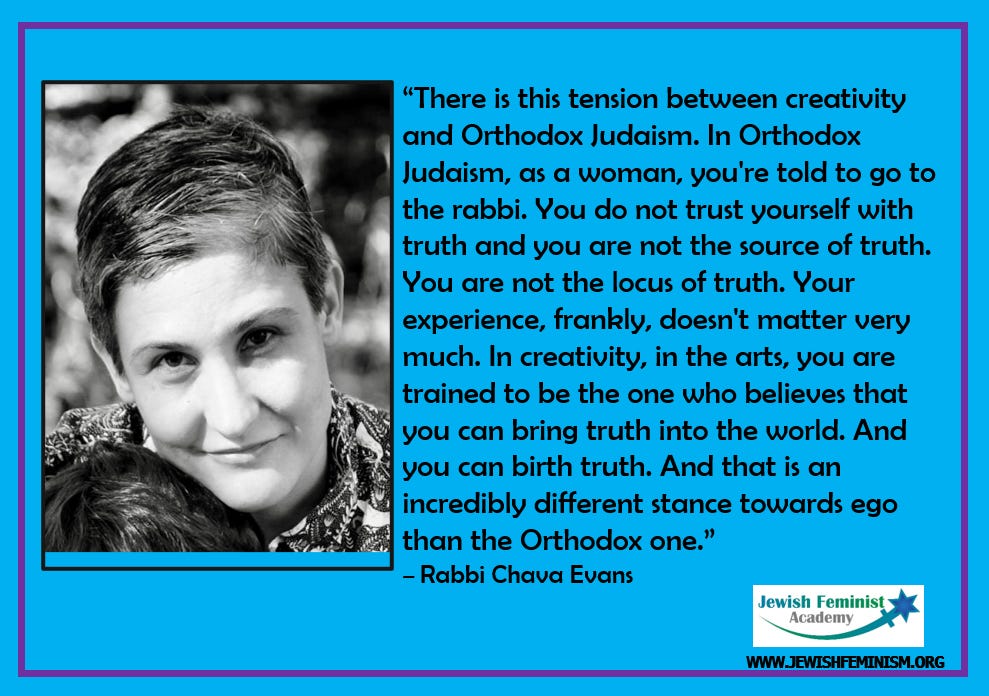

Mostly, I think about what I heard this past week in my Jewish Feminism Reimagined course, from speakers talking about what it looks like to take back our power.

This year, I am thinking about what my Jewish practice would look like if I no longer felt the need to uphold anyone else’s ideas about what is valuable in life.

What would my culture look like if I got rid of all the patriarchal voices inside my own head?

These are the questions on my mind.

What about you?

###